By Tala Raheb – Doctoral Candidate – Emory University

Editor’s Introduction: Tala Raheb was awarded OMSC@PTS’s inaugural Lamin Sanneh Research Prize in 2021. This post reflects on the research she has pursued with this grant. Tala is a doctoral candidate in Asian, African, and Middle Eastern Religions (AAMER) at Emory University. In addition to her work in AAMER, Tala is pursuing a concentration in World Christianity. Her dissertation examines how Palestinian Americans interact with Christian Zionism at the intersection of American religion and politics. Tala received her BA from St. Olaf College, and her MTS from Candler School of Theology.

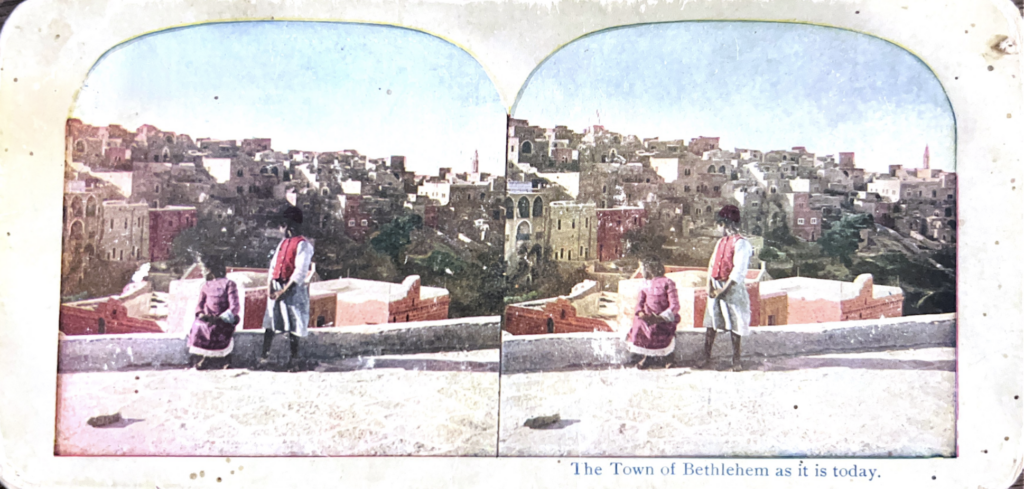

A few years ago, while exploring an antique store in North Carolina, I discovered a box filled with stereograph cards. Stereographs, first invented in the 1850s and popularized in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, are cards with two identical images that, when placed on a stereoscope, produce the illusion of a 3D image.[1] As I sat on the floor sifting through the cards, I stumbled upon a familiar landscape. Bethlehem, my hometown, was featured on a stereograph card. The card read, “This interesting stereoscopic view shows Bethlehem, as it is today. The wonderful story of Jesus, where the child was laid in the manger, so familiar to every Christian, makes this view very interesting.”

The card was part of a Holy Land series, that, much like today’s virtual tours of the Holy Land, is meant to take the Christian viewer on a spiritual journey that ultimately enriches their understanding of the Bible. To find an entire Holy Land collection from the late 1800s is not surprising, as it was during this time that American fascination with Palestine, or to use the words of Hilton Obenzinger, “Holy Land Mania,” was at its peak.[2] By the early 20th century, American Christians were able to travel to Palestine in search of the biblical landscape with which they were familiar. Such as the Arch of Ecce Homo, featured on the stereograph card below. For many American Christians, to travel to Palestine was to participate in biblical prophecy. And with the announcement of the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which declared Palestine a “national home for the Jewish people,” American Christians began interpreting political events as sure signs of the second coming of Christ.

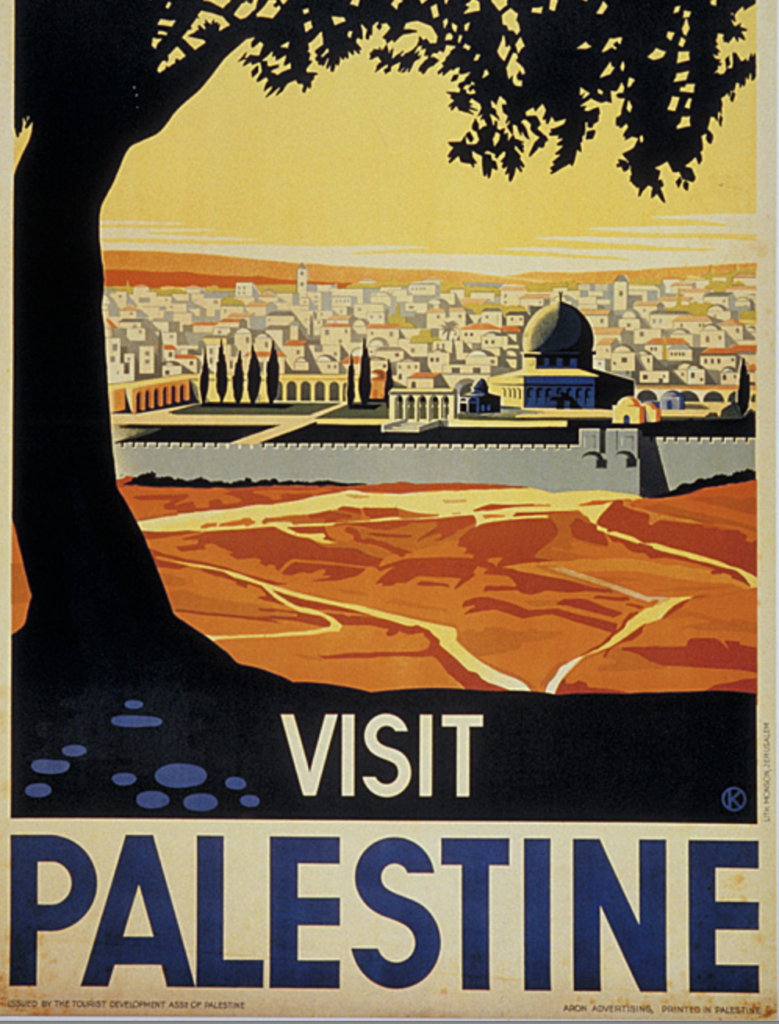

Consequently, travel advertisements encouraged Christians to visit Palestine. As a result, travel narratives and illustrated Bibles became commonplace in each American household. Yet, such advertisements and narratives were not without an agenda. For instance, the “Visit Palestine” poster from 1936, designed by Franz Krausz, capitalized on American Christian obsession with the Holy Land in order to further Zionist aspirations in Palestine.[3] By the mid 20th century, as travel became more accessible to many, traveling to the Holy Land became much easier. Many American Christians could finally walk where Jesus had walked. The political realities on the ground further fueled American Christian enthusiasm for Zionism. Following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, many American Christians adopted Christian Zionist beliefs.

While American Christian enthusiasm for the land upon which Armageddon is expected to occur was high, they had little regard to how such theologies impacted the living stones of the Holy Land, the Palestinian Christians. Many did not even realize that Palestinians could be Christians, even though Christianity came out of Palestine. Furthermore, American Christians did not realize that those living stones were residing among them in the United States. Palestinian Christians, who had immigrated to the US in the early 20th century, recognized the dangers of American Christian mania with the Holy Land.

Palestinian Christians in the US, in the early and mid-20th century, pushed back against the essentialism and reductionism of American Christian pilgrimage and theology. Yet, even upon encountering Palestinian Christians, American Christian Zionists did not see Palestinian Christians as playing a role in the end time narrative. Shalom Goldman explains that American Christian Zionists saw “the Arabs [as] interlopers in Palestine, even if they were Christian Arabs. They had no part to play in God’s plan for the Holy Land and should therefore be encouraged to emigrate.”[4] Following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, Palestine lost a significant number of its Christian residents. Prior to 1948, there were 135,000 Christians living in Palestine, constituting 8% of the population.[5] During the war of 1948, 35% of these Palestinian Christians were displaced, causing them to lose their jobs, homes, and other properties. The Nakba led to a decrease in the percentage of Christians in the Palestinian population from 8% to 2.8% within just a few months.[6] Many of these Palestinian Christians immigrated to the US where they encountered American Christians who were not very interested in hearing their stories but rather in feeling connected to the biblical drama.

Since 1948, American Christian interest in Palestine has only continued to rise. Looking retrospectively at American Christianity enables us to better understand the current relationship of American Christians with Israel and Palestine. The infatuation of American Christians with the place has left them blind to the injustices on the ground. To examine the history of American Christian pilgrimages is also to look critically at American Christian tourism to the Holy Land today. Many American Christians still visit the Holy Land to walk where Jesus walked without interrogating the political context and the occupation of Palestine. Thus, even today, American Christians and the American Church continue to be complicit in the suffering of Palestinians and Palestinian Christians as they turn a blind eye to blatant injustices.

As pilgrimage to the Holy Land continues to be a steady feature of American Christianity, American Christians are called to see the suffering of their sisters and brothers in Christ and to hear and learn from Palestinian Christians and Palestinian American Christians. In doing so, American Christian tours will no longer simply explore the remnants of the biblical landscape but will see Palestine and its living stones “as [they are] today.”

—

[1] “Stereograph Cards – Background and Scope,” 1860, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/stereo/background.html.

[2] Hilton Obenzinger, American Palestine Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania (Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, Project MUSE, 1999).

[3] “‘Visit Palestine’: A Brief Study of Palestine Posters,” Institute for Palestine Studies, accessed June 30, 2023, https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/190753.

[4] Shalom Goldman, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, and the Idea of the Promised Land, New edition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 24.

[5] Mitri Raheb, Meredith Riedel, and Mark A. Lamport, eds., The Rowman & Littlefield Handbook of Christianity in the Middle East (The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2020).

[6] Raheb, Riedel, and Lamport.