By Davi C. Ribeiro-Lin – Assistant Professor of Pastoral Theology & Ministry – Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary

Editor’s Introduction: Dr. Davi C. Ribeiro Lin was awarded OMSC@PTS’s inaugural Lamin Sanneh Research Prize in 2021. This post reflects on the research he has pursued with this grant. He recently joined Gordon-Conwell as an assistant professor of pastoral theology and ministry. His interest in pastoral theology and ministry have been shaped by an interdisciplinary perspective; he is trained in practical theology, counseling psychology, and the pastoral perspective of Augustine of Hippo. Dr. Ribeiro Lin has served for a decade as an evangelical pastor in Brazil, covering a wide range of areas within the church, including preaching, teaching, discipleship, pastoral care/counseling.

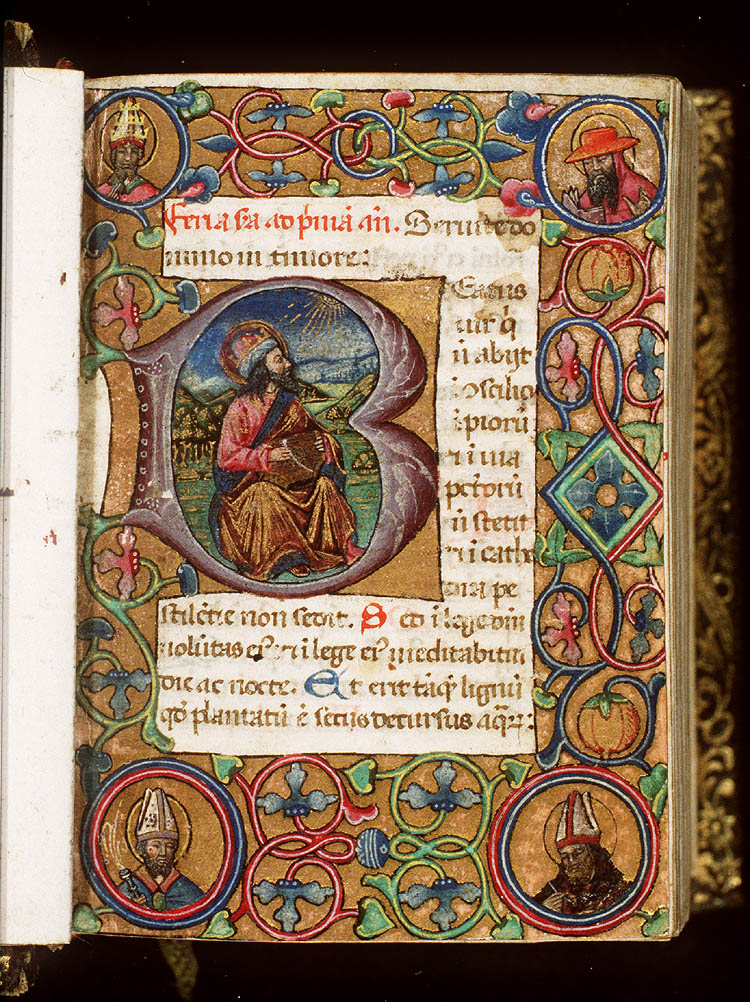

Can theology in a narrative form convey a therapeutic experience? During my doctoral work, my thesis suggested that Augustine of Hippo (354-430) in his Confessions (397-401) is not merely writing an auto-biography but a theography, an other-centered narrative of a person-in-relation that uses the motif of confession (‘opening the wounds of sin’, ‘praising the doctor’) to stand as a patient “my pen serves me as a tongue” (Conf. 11.2.2) before Christ the Physician (Christus Medicus). As God becomes Augustine’s inward healer, his Confessions was a therapeutic act for its writer, an “effect upon me in my writing of them, and still do when I read them now” (Retract. 2.6.1).

Furthermore, Augustine sought to elicit in the reader a health-oriented response, “that recital arouses the hearer’s heart, forbidding it to slump into despair” (Conf. 10.3.4). In other words, the narrative of the difficult parts of Augustine’s life is not meant solely for himself and the recovery of his heart, but primarily to generate hope and health to our restless heart (Conf. 1.1.1). Following Augustine of Hippo’s vision to write Confessions with the intent to convey hope amidst distress to his wider audience, I have earnestly sought to understand if Augustine’s perspective has the potential to become a therapeutic resource in twenty-first century societies. At the time of my doctoral defense, I did not have the opportunity to test its applicability through a methodology that would make this vision a concrete practical intervention. But that soon changed as I entered the classroom.

Over the last few years (2019-2022), graduate students of theology in Seminário Teológico Servo de Cristo in São Paulo (Brazil) have written their personal theographies having Confessions as a template, retelling a particularly difficult life stage or stressful life event. After courses on the therapeutic vision of Augustine’s Confessions, these students have recognized in Augustine a reference for retelling their own personal stories, recounting an existential journey or personal stressful experience in a theography. The form has been, as Augustine proposed, an I-thou prayer to their divine doctor, in which personal biographies of fragmentation and loss were trespassed by the poetic language of the psalms and Augustinian theology of grace.

This rich, meaningful, personal material has convinced me these students not only were able to lay ears to Augustine’s heart (Conf. 10.3.4), but their theographies increased the sense of being under God’s benevolent care and fostered vulnerability, gratitude and humility. Wounded memory, when trespassed by the arrow of grace and put pen to paper, narrated a vulnerable existence with God in its brilliance. As Paul the apostle suggested, in retelling painful experiences, “where sin increased, grace increased all the more” (Romans 5:20). As contemporary culture flirts with individualism and narcissism, often Christian leaders have developed their abilities before their character and virtues. I understood these theographies in an MDiv program were constituting an antidote against leadership cultures that are not shaped by a deep awareness of grace and humility.

Moreover, it has become clear that students could respond best to Augustine’s proposal by expressing the difficult parts in life through narrative writing of their life events, weaving biography into theological meaning. Of particular importance is the intrinsic connection between making meaning and narratives, for stories configure dispersed events into a coherent whole, a narrative meaning making and narrative integration of life events. Life narratives structure experience reinterpretation, organize memory and reappraise negative and distressful events. Rewriting one’s narrative therapeutically aligns with what Augustine had intuited (Retract. 2.6.1), that writing is a powerful technique to reconstruct a stressful or traumatic life event.

Although Confessions addresses God as the doctor of Augustine’s inner life and intends to stimulate health, it is striking that there has never been a systematic study of its therapeutic vision and effects. The connections for such endeavor are ripe when one considers that, over the last 30 years, Religion, Spiritualty and Health (RSH) research has firmly established the connection between spirituality and mental health, creating favorable conditions for interdisciplinary dialogue and empirical verification. Realizing there is further work to be done, this intuition evolved into a research and intervention project, named “Theography as Cura Animarum: Augustine’s Confessions as Narrative Meaning Making for Mental Health”. This research aims to verify mental health related effects of Augustine’s theology through an empirical narrative writing model, that is interdisciplinary in its concept, fosters meaning making to generate redemptive stories and can be assessed in its health outcomes. It will hopefully result in (I) critical reconstruction of Confessions’ theology in dialogue with psychological research (II) understanding of the pedagogical process that stimulates therapeutic narratives across cultures (III) cross-cultural results on narrative meaning making and mental health.

Bruner (2004) argued that life narratives are variants of culture’s canonical forms, shaped by cognitive and structure linguistic processes, coauthored by the person and the cultural context in which meaning is inserted (McAdams, 2001). By hearing both gospel and culture, as well as bringing inspiration from church history, this project will be able to recognize which themes, concepts and images resonate more poignantly and how Augustine’s legacy fertilizes the dialogue between narratives of self, theology and culture.

In his inaugural lecture for OMSC at Princeton Theological Seminary (Sept. 2020), Andrew Walls suggested that, as the center of gravity of Christianity has shifted from the West to the Global South, the continents of Asia, Latin America and Africa have become “theological laboratories” fully as much as Europe and North America. So far, Servo de Cristo Seminary in São Paulo (Brazil) has been our thriving “theological laboratory” for theological narrative writing and meaning making. As I transition to a full-time position in Massachusetts, USA, at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and remain a visiting professor in Brazil, the project has now the opportunity to serve globally. Gordon-Conwell is a place with a significant representation of diverse nationalities, especially Asian and Latin-American students, but also African, European, and Oceanian students. These new theographies will allow the hearing of a truly worldwide conversation and cross-cultural comparison. These narratives will hopefully include participants with their migrant stories, as Augustine’s own heritage as man living between cultures, the “Mestizo” Augustine (González, 2016).

As the current global health crises calls the church to once again examine and redefine its role, this project also carries a specific contribution at the intersection of mission studies, Augustinian studies, and church history at large in re-visioning the mission of health. As it advances the contemporary relevance of Augustine’s legacy in its promotion of mental health, it reminds us that Christianity has been engaged in healing since its commencement. Although conceptions of health have changed over the centuries, the absence of a theological comprehension of therapy is the product of a concept and a task that has been largely secularized. Although the task of therapy and mental health in contemporary societies belongs primarily to psychology, a theological perspective on health and therapy is not to be sidelined. Research about Augustine, therapy and health points to an open field for theologians and reminds them not to neglect a topic that is very much present in the gospels. Christ’s role is associated with that of the medical doctor that heals the sick, carries the diseases, and forgives the sinners. He is the agent of life in its fullness that overcomes physical, interpersonal, and spiritual illnesses, an emphasis Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions can help us once more retrieve. Augustine, however, did not have the privilege we have been given in the 21st century, as Christianity became a global phenomenon. The recuperation of the therapeutic task of theology can now happen in a period of major worldwide theological expansion within global Christianity: boiling pots of spiritual energy and redemptive health-oriented narratives coming from all over the world.